A mini treatise on human governance

Words & images © Paul Ransom

1: A brief statement of intent

Before we go any further, let me lay a few cards on the table. I am biased. My view is limited and, no doubt, flawed in some measure.

Furthermore, I am not an academic. I have not formally studied political science or history. Likewise, I have never belonged to a political party. Although I was broadly leftist in my younger years, and have never voted for a candidate who advertised themselves as conservative, my view has evolved over time towards a less ideological blend of ideas that some would call centrist; but that others would deride as weak and non-committed.

Meanwhile, some of my friends and colleagues think I’m too ‘woke’ and others regard me as not sufficiently ‘awake’.

Given this, why would I commit the time and effort required to lay out the proposition below? As an amateur, internet nobody I have no cachet, no audience and scant chance of making a dent in the body politic.

In short, I am doing this because, like many others, I hope against hope for a reimagined politics. For something less toxic. Less jihadist.

As such, I will not be sporting a MAGA cap, fretting about pronouns, or planting a flag on the front lawn. Neither will I be trumpeting the righteous anti-elite rhetoric and paranoid populism that clutters social feeds and makes celebrities out of hyper-opinionated podcasters.

What I will be doing is outlining a vision of a more honest, more humane form of politics.

2: A new real

Imagine a politics that genuinely took people into account. Not merely as voters or consumers, or as anonymous constituents in demographic models, but as fully-fledged, flawed human beings who are at once individual and social.

This may seem airy-fairy. Indeed, in the current climate of weaponised certainty, where those who differ from us are routinely demonised, a more humane discourse appears to be little more than a forlorn fantasy.

I confess, perhaps it is. After all, the reality of politics is more often about the possible than the preferred. However, mine is not a utopian dream. Rather, it is grounded in a hard-headed acceptance of our shared imperfections. This is why I call it psycho-politics.

In saying this, I acknowledge that the present practise of politics recognises and leverages our individual and group psychology astutely; but it does so in a largely predatory and exploitative fashion. The tactics of divide and conquer, and the cynical simplicities of demagogues are perhaps the standout examples.

- I think it is fair to say that we currently find ourselves in a moment of amplified division. The so-called culture wars are now a shouting match. Billions of megaphones blaring. Even if this trend is mere theatre – the optics of which mask a deeper unity – I still find it unsettling, and the cynical side of me cannot help but wonder who is benefiting from our descent into holy war. Who will occupy the middle ground we are busily vacating?

Yet, though the tribal nature of ideological dispute appears intractable, and the brute realpolitik of win/lose baked in, we only need look up from the battleground of the mid-2020s to glimpse the wider perspective. History shows us that even the status quo changes. Norms and values evolve. Things once commonplace become unthinkable, just as those formerly exiled may one day come to be embraced.

Here perhaps lies the bleeding edge of hope and fear. For some, progress is too slow. For others, change comes too fast.

This is a major fault line in our psyche, one that plays out in our private lives and public domains. It shapes our attitude to risk. How broken must it be before we fix it?

Although the hope/fear axis is navigated more by intuition and emotion, our cultural and political responses have typically been channelled through the rationalised prisms of academia, ideology and commentariat. We talk in abstractions. Dialectics, class, economy. Rights, rules, justice. While this is fine for essay writing, legal argument and parliamentary committees, it frequently fails to speak in a language that seems real. Human.

This entrenches an imbalance, and creates an opportunity for those who know more to manipulate those who know less. Unfortunately, the resulting simplifications, (although sold as liberty and/or deliverance), are another form of lock-out.

Thus, what I am proposing here is not a dumbing down but a levelling up. A change in the way we speak with one another.

- For more on this, see Whatever Happened To Adult Conversation.

If at present we are over-stimulated and anxious, subsisting on a 24/7 abundance of highly processed goo, imagine a calmer, more balanced diet. Picture an off-button. Extending the metaphor further, think of psycho-politics as detox. Therapy for those at once deafened and unheard.

3: Building blocks

When we think politics, we tend to cluster around standard banners. Capitalism, socialism. Dictatorship, democracy. We sometimes cite the great theorists. Rousseau, Locke, Marx, et al. We may also incorporate economic thinking. Keynesian, neo-liberal, etcetera. Usually, we overlay this with things like party preference, personal values and the biases of upbringing.

None of this is intrinsically illegitimate. However, in the main, it devolves to overly stark black/white thinking. The individual or the collective. Market forces or regulation. Jobs or trees. Partly, this is due to the adversarial nature of politics, partly to the way that media amplifies contest over consensus.

But to stop here would be to overlook the elephant – because there is something deeply embedded in the human animal that inclines us towards either/or. It did not require elite conspiracy to make us tribal, hierarchical, and prone to convenient catch-all prescriptions.

To borrow a truism from economics; where there is broad based demand for certainty, the market will supply it.

This is why I am deviating from the norms of ideo-political construction. Psycho-politics tries to view the landscape through different lenses.

- Evolution

- Anthropology

- Cognition & neuro-science

- Group & individual psychology

- Network theory & bio-mimicry

In addition, I can confirm a bias you may already suspect. Despite doing my best to filter for it, my underlying value set is broadly civic/humanist. Meaning, I do not regard ethnicity, gender, class, sexuality, voting history or (dis)ability as being automatically deserving of either privilege or a lack thereof. Ultimately, we are all as dead as each other.

Furthermore, humanity is no more entitled than any other species to its place on Earth. If we choose to obliterate ourselves, so be it.

Perhaps this last point is the point. I share this with you now, in spite of the near futility of the exercise, because I am wired to care about you. Because I still choose to care. Even if you think I’m stupid or asleep, I still want you to survive. More than that…thrive.

4: What is politics about?

At the core of standard political and economic debate is a simple, yet profound challenge. How do we wish to live together?

- What is the best way to organise ourselves?

- What is the best way to coordinate our activities?

- What are the rules of engagement and how do we enforce them?

- How do we balance competing interests and resolve disputes?

- How do we protect ourselves against external threats?

And, drilling down further:

- How do we manage the use and distribution of resources?

- How do we apportion rights and responsibilities?

- How do we balance individual and group objectives?

As much as these may be political or philosophical conundrums, they are also existential – for these challenges not only pre-date the emergence of modern politics but were present long before large scale, fixed settlements and early city states. These problems are common amongst social species. They cut to the core business of survival. Moreover, sociability itself is an adaptive response to the problems posed by an uncertain, ever-shifting environment. Social animals thrive because joint ventures work.

But groups are beset by various frictions, especially where sexual selection mechanisms drive competition between individuals. Clearly, this can be a downside, leading to a loss of cohesion, and group fracturing. Yet, robust internal competition is vital. It promotes vigour. Drives innovation.

However, the ongoing process of evolution does not require us to choose between competition and co-operation, it challenges us to strike a sustainable balance.

Unfortunately, when seen through the lens of abstracted and reductive ideology, we too often forget this. Today, we talk politics as if we were not animals. As if we had a right to life; which, in the grander scheme of nature, we simply do not.

I say this not to dismiss or pathologise our capacity for abstract thought. After all, it too is an adaptation. All of our abstractions are rooted in our reality. Civilisation is a response to ecological pressure.

My issue is the forgetting. Or, as I have called it elsewhere, the Central Denial.1 What I mean by this is that we have privileged abstraction to an unhealthy degree. We have abstracted ourselves out of reality. We gloss over the fact that we are social-hierarchical mammals, creatures almost entirely dependent on one another, and whose survival is contingent on benign biospheric conditions. We have rationalised our fear of death into a pantheon of everlasting fantasy, and bought into the myth that ‘reason’ and ‘virtue’ have final dominion over unconscious impulse and cognitive bias.

Whilst countless kings, priests and sundry swindlers long ago sensed the deeper currents of human psychology – and tapped them for millennia to convince and corral us – relatively recent advances in our understanding have super-charged the ancient art of persuasion. In tandem with increasing population size and density, and more refined methods of mass communication, this has enabled us to target unconscious triggers more effectively.

And so…while the hook is fear, and the bait appeals to our desire for predictability and control, the catch is sold in the guise of reason. Thus, manipulation may scan as choice. Cost as benefit. Atrocity as acceptable.

Psycho-politics addresses this by removing the mask and sharpening the focus. When we correct for the blur of ideology and denial, and frame our politics as an evolving response to matters of sustainable survival, we can begin to have a more measured discussion. A more transparent and inclusive rationality.

When we understand that our baseline premises, our core KPIs, are organisational and existential – rather than empire, entitlement or point scoring – we reduce the drama of conflicting values. We recalibrate the debate from me or you to me and you. In doing so, we allow ourselves to use a more honest language.

The less we create incentives to lie, the more truthful we can be.

5: Who are we?

If the wellspring of politics is the tribe, and the need to negotiate relationship and resource allocation, this suggests two clear areas of focus. Ourselves and the environment we live in.

In survivalist terms, we must learn to live with both. Adapt to both. (Or die.) As individuals we do not exist in a bubble, and neither do we as a species. Much as we are drawn to the idea of the self-contained, self-authoring individual or in-group defiantly walking their chosen paths in spite of adversity, the reality is less heroic. Look around, and you will find yourself located in a complex web of exchange. Not just enmeshed, dependent.

To put it bluntly, relationship is fundamental. How we relate is how we survive. What this asks of us politically – culturally – is to get clear about who we are. Although spiritual tradition, ethno-nationalist stereotype, and a myriad of class and gender beliefs have overlaid our self-perception with a foreground of bias and habit, we can still filter for these distortions. When we zoom out from parochial and anthropocentric assumption and consider ourselves in the wider context of environment and evolution, we make space for a story of self we can all take part in. The animal one. The one we recognise as our common humanity, or that we like to call human nature.

The stumbling block here is our near universal refusal to accept ourselves as we are. With respect, I think it is fair to suggest that we are, amongst other things, the arrogant ape. Over time we have spun a collection of stories about how special we are; from being anointed by deities and given dominion on Earth, to being the universe’s preferred candidate for immortality and grand unifying consciousness.

Control more, reason better, vibrate higher…and sure enough we will become gods.

In fairness, this is not entirely hubristic. As a species we are evidently a class apart from all others on this planet. We have leveraged our evolutionary endowments in a way no other animal has. We have a capacity for tool making, reasoning, abstract thought, and shared learning that helps us overcome physical disadvantage. Our relatively slow, weak, hairless bodies, and the long term vulnerability of our young, have been amply offset by our smarts.

However, intellectual dexterity comes bundled with psycho-emotional complexity, one that often runs counter to the more triumphal arcs of the homo sapien saga. We live this schism, and we see it reflected in those we love; and together, we have written reams about it. This is the heart of the human story.

Tellingly, our convoluted mental landscapes map out in our social institutions, and especially in politics. Despite the veneers of rationality, impartiality and ‘wanting what is best’, we operate (individually and collectively) within the parameters of frequently unacknowledged and unconscious cognitive bias. In short, our brains are networked to privilege some forms of information over others, and this profoundly effects our perception and decision making, thereby skewing us towards preferences and behaviours that fit.2

Ad agencies are all over this. So too Hollywood. Meanwhile, smart attorneys employ these insights to sway judges and juries, and the disseminators of dis and mal information do likewise for any number of reasons. The political class are merely the headline act.

So, what are these levers, these all-too-human strings that make some puppeteers and others marionettes?

- Broadly, we are more likely to respond positively to (and recall) information that is fast, simple and affirms our worldview and sense of self

- Our attention is drawn to the dramatic and emotional, and as such we are affected (influenced) more by spectacle and appearance than by substance and detail

- The way that memory works means that more recent information is not only more easily recalled but has a greater impact on opinion

- The more we hear something the less novel and, therefore, threatening it seems; thus making it more likely that we will accept it as either fact or banality

And then there is fear. We are a threat averse species. This underwrites our habit of baulking at change and clustering around apparent certainties. It also drives our taste for negative news, nudges us to see enemies everywhere, and amplifies our preference for the cosiness of the past over the unknowns of the present and future. Although there is a sound evolutionary rationale for all this, the contemporary realities of politics and society are not those of small hunter/gatherer clans living in close proximity to one another and their environment. (More on this later.)

Other related biases of cognition and perception worth knowing about include:

- Coherence bias: the desire to have the world ‘make sense’ and accord to predictable patterns

- Affiliation bias: the desire to belong to and identify with in-groups – call it tribalism

- Status quo bias: our tendency to stick with what we have, to find orthodoxy less risky

- Hindsight bias: our tendency to downplay past suffering, which in turn feeds the widespread view that ‘things are getting worse’

If I am a seller of snake oil, and I know you don’t know this, I’m hiring a bunch of snakes. In jargon, this is called an asymmetry. An exploitation of such.

Thus, psycho-politics is grounded in a redistribution of the knowledge base. Moreover, it is rooted In a profound and perhaps uncomfortable challenge to the present norm. Can we accept ourselves? Are we ready, as individuals, and as a species, to remove the blinkers and confound our own denial?

Even if we question the findings of decades of cognition research, and dispute much of the practise and theoretical specifics of psychology and psychiatry, it is not unreasonable to conclude that we now have a more accurate and detailed picture of ourselves. Thus, while our understanding remains incomplete, the take-out is increasingly clear. In this instance at least, knowledge truly is power.

6: Where do we live?

There is much talk of community, and of how we are all located within it. Conversely, others argue that there are ‘only’ individuals, and that society is merely a by-product. Both views have spawned extremes. Both have a huge blind spot.

Earlier, I spoke of the Central Denial; our common habit of downplaying or explaining away what and where we are. Here again, my intention is not to stigmatise but to acknowledge. The Anthro-bubble is, to a degree, understandable. Like any other animal, we wanted to put space between ourselves and that which threatened us. We sought protection from predators and the elements, and strove to create a buffer against privation. We took sanctuary in order and the predictability it conferred. As our sense of control grew, we doubled down. If the default of nature was perpetual war, we began to feel like conquerors. Ultimately, we pushed the frontiers of our empire out towards the domain of our most feared foe. Indeed, those who hype AI are already insisting that we are but moments from defeating death.3

Zooming out, what we notice is a long term trend. We are distancing ourselves from nature. Yet, perhaps more significantly, we have othered nature. Psycho-culturally – conceptually – it is now an externality, something we shape and study, or admire, or get back to. Intellectually and intuitively we may understand that no such distance exists, yet we mostly behave as if it did. Consequently, much of our political and economic discourse fails to seriously value nature, let alone register it as a foundational, definitive presence.

- For more on our perplexing relationship with the environment, see The ‘Nature’ Problem.

Yet, it does not require genius or great virtue to recognise that we number amongst trillions of dynamic elements in a constantly morphing network of biospheric exchange; nor indeed that we remain dependent upon natural processes and the resources and conditions they create. We live in a thin atmospheric strip, preferring the planet’s more temperate zones. We are entirely reliant on the availability of fresh water and of edible plants and prey. We remain vulnerable to storm and sea, as we do to bacteria and other pathogens.

Any notion that we have – or are entitled to – dominion is delusional. Suicidally so. Ever-increasing consumption will inevitably over tax the resource base. Even with dramatic efficiency gains and tech fixes, we cannot operate as though Earth were an unemptyable cupboard. Or something we can render in our own image. A human-centric mono-culture is highly unlikely to flourish.

Furthermore, if we pause to contemplate the upshot of evicting nature from our lives, we will soon realise that it is not a project worth pursuing. Living sustainably is not just about electricity and protein; it is also about how it feels. Where the joy might be found. Where the wonder. The sense of connection.

Present day politics somehow misses this – not so much in spite of but because of the attention that green issues receive. The politics of environment is largely theatrical, couched in terms that are either reductively economic or distractingly moral/ideological. We argue about global warming, conservation and biodiversity as if nature were a toy we were squabbling over. As though it were something that needed saving, or could be made more profitable.

- Let me be unequivocal here. It is not nature that needs saving. The planet neither relies upon nor cares about us. The biosphere will be either more or less conducive to our survival. Or indeed hostile. Its time scales dwarf our attention spans and its forces can easily overwhelm our flimsy encampments. If, through ignorance, greed or arrogance, we tamper with the mechanisms of nature too much, the network may readjust in ways that leave us dangerously disconnected. We are expendable.

The true politics of environment is about survival. How can we live together with this ecosystem? What can we do/not do to help the earth sustain us?

This may sound dry – another example of over-privileged, possibly partisan intellectualisation – yet behind the rationalised edifice is a deeper pragmatism. Not simply the physical practicalities of survival, but the subtle, psychological necessities of thriving. Not just the how, but the what for and the why bother?

7: The state of the tribe

In contemporary democracies you will often hear people bemoaning the short-term focus of the competing candidates. It is often cited by cynics and conspiracy theorists as proof of everything from selfish incompetence to sinister machination. Yet, when we draw back from the dramas of smugness, outrage and jihad, we are able to place this myopic default in its longer run context.

Politics is short-sighted because we are. We routinely overlook the bigger picture. Immersed in self and modernity, we forget that our present day forms emerged from prior designs. The ‘state’ is the new tribal council. Clan elders are now cabinet members. Indeed, we formed our first government long before we built our first office.

Humans are complex social animals, and our evolved preference for group living drove us to make rules. As other species did, we arrived, (whether by instinct, experiment or a blend of both), at codes of behaviour that made it possible for numbers of self-motivated individuals to share in the upsides of cooperation. Unity and organisation paid off.

It is sometimes said that all politics is tribal. This is truer than we typically imagine. Politics begins as a response to tribal living; a means of resolving its inevitable conflicts.

However, the slower engines of evolution did not keep pace with human ingenuity. At some point the tribe became the city, became the empire. The chief became Caesar. The elders the priests and palace insiders.

And then…somewhere along the line…we lost sight of each other. Tribal elders no longer sat around the fire with everyone. A circle of friends and family became a country of strangers. The effect of this shift remains profound.

- Elsewhere on this site, I investigate this phenomenon further. See Abstract Secessionism.

Today we find ourselves in super-sized communities, and our re-branded elders are mostly distant from us. Governments and related institutions operate at a remove. As such, they tend to reduce us to numbers. Meanwhile, we are in the habit of caricaturing them as incompetent, corrupt and uncaring. Or, worse, as saviours. Together, apart, we have dehumanised ourselves and made our politics increasingly unfit for the purpose of serving said humans.

Our commonly rationalised response to this has been framed by recency bias and by our deep desire for simple, consistent explanation. Meanwhile, emotionally, many are troubled by a sense of decline, disenfranchisement, permanent crisis and paranoia.

Add magnification and megaphone and soon enough you have madness.

By lengthening our historical focus, and broadening our view from the narrow amnesia of standard ideology, we are able to recast our politics in a way that remembers who we are.

In this light, the much demonised state is seen instead as part of an ongoing, trial and error process of mediating tribal life. Its centralised structures and impersonal nature can also be understood as problems arising from scale. Small, personally bonded clans of a few dozen present a different set of governance and resource challenges than those of huge, multi-million strong nation states.

When it comes to government, size matters. A lot.

The other thing worth saying about both politics and government is that they are predictably human institutions – meaning, we cannot reasonably expect them to be error-free, immune to the projects of ego, or beyond the distorting effects of win/loss and other perverse incentives.

Once upon a time, the tribe gathered to share the load. Then, as it grew, the tribe became its own burden.

Just as the individual may be crushed by the might of the tribe, the tribe may buckle under the weight of its individuals. Same goes on the plus side. I am carried by the tribe, and in turn I lift it up.

8: Finding common ground

My intention thus far has been to establish the underpinnings of a more honest politics – a way of thinking about governance that allows us to transcend the reductionism and abstractions of orthodox ideology and move forward in a more grounded way.

I have suggested that in order to humanise politics, we need more clarity around what ‘human’ means. For this, we are best advised to zoom out from the distracting spectacle of present day polarisation and see ourselves in the wider perspective of nature. Evolution and environment. Thereafter, we can better understand what this tells us about both society and individuals.

In turn, this helps lay bare the manipulative mechanisms of persuasion that drive standard politics, legitimise power structures, distort perception, amplify division, and fuel extremist reaction.

Here we may be tempted into the reflex of system blaming, or to indulge in the self-validating habit of righteous condemnation. Yet, this is where we need to remind ourselves that all politics – corrupt or otherwise – is people powered. We the people are the tyrants, the liars, the ones who ‘do what it takes’. Even if we are indeed ruled by a cabal of Zionist paedophiles, as some insist, my bet is that even these demonised, deep state elites are human.

In order to author the change, we must own the status quo.

Remember, divide and conquer only works because we buy into it. Because both self and other are easily essentialised. The in-group (we) are decent, hard-working, deserving of reward, and so on. Out-groups (they) are immoral, lazy, deserving of sanction, etcetera. These simplicities tend to become more entrenched, more readily weaponised, the further apart we are, or are kept. Where the other is distant they can be abstracted. Dehumanised.

- Suspected

- Excluded

- Hated

- Exterminated

To clarify, my aim here is not to scold you or except myself from these very human proclivities. Indeed, suspicion of, and violence against, out-groups – neighbouring prides, rival packs, competitor species – is common across the biosphere. We just rationalise it more.

But anyone who has seen You Tube videos of cats befriending birds and dogs rearing piglets will be reminded that personal contact goes a long way to dissolving seemingly profound animosities.

Here then, the common ground of a recalibrated psycho-politics. The place we stop to meet the other. Even though the sheer size of our societies bakes in impersonal distance (and the resulting abstractions), we owe it to ourselves to create and explore channels of reconnection and relationship. To remember. We all desire. We all suffer. We all die.

- Reach across the aisle and there you will find someone more alike than unlike. This is neither a great secret nor a pearl of amazing insight. Although some people are hard to like, some are predators, and others best avoided, this too reminds us how similar most of us are – for there is not a society anywhere that values lying, cheating and cruelty above honesty, kindness and fair play. Indeed, perhaps much of our bubbling disquiet with the hyper-individualist, monetised edicts of consumer capitalism, and with the censorious and punitive codes of status obsessed honour culture, is that they run counter to our deeper desire for connection, belonging and free exploration. For something less trivial than the latest fad. Something greater than self alone.

As such, psycho-politics is a trickle-up response to a top-down norm. Think of it as micro-activism on a mass scale.

If, as many declare, things are broken, we cannot remain idle, merely complaining while we wait for an imaginary repair van. Neither will pinning our hopes on apparent saviours make everything great. Nor will the typically blunt and bloody ructions of revolution.

All the while politics plays out like an elite sport, something we merely spectate rather than take part in, it will be used to varying degrees against us. Because power is as much ceded as it is seized.

This may seem cliché, but our common ground is one another, and for this to find its way into the landscape of politics and governance we need to practise it. Not yell it, act it.

Whether we like it or not, as members of the tribe we are already engaged in politics, even if only at the fringes. (Indeed, even saying that you are not into politics is a political act; a kind of vote.) However, there is more to participation than stuffing a ballot box or sharing a blog post. I do not mean that we should all take up party membership or read Aristotle, nor indeed obsess over the minutiae of legislation, but rather that we can take a more active role in politics by not taking part. By which I mean, not fuelling and amplifying race-to-the-bottom incentives for politicians to exploit unconscious bias and asymmetries of knowledge. If we truly desire something better than blunt win/loss politics then it falls upon us not to laud the conqueror.

If this sounds too difficult or fanciful – or indeed too abstract – use a shopping metaphor. If I like to live near good cafes, it falls to me to help local coffee shops remain viable. Just as there are in the economy, there are ‘market signals’ in politics. Thus, whilst the current supply tastes a lot like poison, it is in our hands to detoxify the demand.

- To see how the shopping metaphor might help clarify what this post is trying to say, check out We Buy Ourselves On Credit.

In the new psycho-politics, individual actions matter. Begin by arming yourself against predatory and manipulative messaging. Take a breath, pull back from the heat and drama. Don’t fan the flames. Remember, those you disagree with likely share similar core desires and values.

Moreover, politicians are as flawed and irrational and prone to bias and temptation as you are. They are not messiahs, nor are they always the hopelessly corrupt monsters of popular complaint. A crusade against politicians will yield nothing but more politicians.

Humans are conflicted creatures. We have contradictory impulses. Much as there are better angels, there is grasping, selfish impulse. Our politicised, 21st century culture war is currently mired in a negative feedback loop, where we daily reinforce our taste for tribalised absolutes and silver bullet solutions. The drama may be addictive, but the binge is unhealthy.

To flip this, to start generating a positive feedback loop, we need to take responsibility. Personally. The root of all social/cultural constructs is the way we choose to act as individuals. The system is the habit of our behaviour. Therefore, the upward spiral begins with each of us. With what we think, say, and ‘hear’ about the other. With a more honest awareness of self. With our instinct for kindness and compassion, and our ability to empathise.

There is indeed a bulwark against tyranny, war, and unsustainable madness. But it is not the Constitution. Nor democracy. Not even the free market. It is the ground we all walk upon. That which no president can mandate or ban.

And if that sounds a bit too virtuous, frame it as a numbers game. The mob vastly outnumber the palace guard. The emperor is clothed in our consent, passive or otherwise. To pretend that we are powerless is lazy. A poor me whinge. A toothless fatwah.4 Therefore, rather than raging or bragging about how ‘awake’ we are, we can start to exercise our power in the concrete, inter-personal spheres we all inhabit; especially when the megaphones are trying to drown out our unspoken recognition of shared humanity.

9: How to argue

Disagreement is not only inevitable but desirable. Although many of us try to avoid conflict, and become flustered or overheated in arguments, a rigorous contest of ideas is a means of refining our beliefs, challenging our assumptions and gaining insight into the perspectives of others. In fact, a constructive debate can lead to better outcomes for all parties, as rival theories synthesise into new understanding. Or, in the case of politics, viable consensus.

The issue is not that we have opposing views but the way we handle our differences. Just as they can at home, so too our social disagreements can become bad tempered, dysfunctional and violent. Religion and politics are notorious for taking their arguments too far.

Although we may urge people not to get so hot headed, if we are honest we must also acknowledge that we love a good fight. Conflict is compelling. In fiction, in sport, between rivals at work. Not only do we like the drama but we like to pick sides. Once again: tribalism, belonging, and the sense of identity that comes with it.

Cynical politics knows this. News media and algorithms feed on it. Amplify it. If the current state of socio-cultural discourse resembles a sandpit squabble, it is partly because we find it so entertaining.

The irony is that our taste for conflict tends to over-simplify the resulting arguments, and therefore dilute the benefits of competition. In a pristine arena of perfectly reasonable parties, the process of debate helps filter out the extreme and unworkable in favour of the more pragmatic and modulated. Everyone updates their positions, the ‘truth’ remains a work in progress, and nobody is tempted into certainty or insisting on an all or nothing resolution.

Evidently, this is not the world we live in.

As a result, some look longingly backwards to an imagined golden age of dispassionate philosopher kings, while others crave the reset button of system collapse or strongman authority. Meanwhile, red faced blow-hards and assorted know-it-alls on news channels and social media queue up to pound their desks and offer their own versions of ‘if only this, then…’

- NB: Apologies if you feel I am guilty of the same. Though I may be falling short in the attempt, my intention here is not to proffer absolutes or quick fixes, nor to blame any party above any other. Indeed, I am forwarding the argument for a new psycho-politics as a start point, not a final solution. (More on this in the conclusion.)

However, the way to reverse a self-reinforcing trend of polarised dispute is not to enforce agreement. When orthodoxy is compulsory, and deviation comes at intolerable personal and professional cost, the result is stifling. The species that cannot adjust, likely dies.

This is why politics should remain adversarial, with multiple inputs vying for consideration. This reduces rigidity, puts ideas to the test and encourages innovative thinking.

Furthermore, a degree of passion is understandable. We all have a stake in the law, the economy, and the environment (built, social, and natural). We also like to see our personal values reflected in the formal institutions of our culture. No matter how fearlessly individual we tell ourselves we are, almost none of us would relish the prospect of citizenship in a nation of aliens.

The deeper challenge is not to win the argument but to find a way to keep arguing. As I suggested in the previous section, this begins with each of us, with how we speak and, significantly, how we listen. We may never arrive at ultimate truth or design the perfect society but we can take charge of our own behaviour.

Politics is a conversation we have with ourselves. The tribe talking to itself in the mirror. And we all vote with our voices.

10: The ‘beta’ perspective

I have used the word honesty a few times in this piece. To explain, what I am implying is not that we can realistically hope for politics without individual lies, (just as you and I can never seriously claim or promise to be entirely truthful). Rather, what I mean is that, if we try, we can train ourselves to look up from the dazzle of current conflict, correct for the distortions of bias, and zoom out from the numerous bubbles that distract us and confine our thinking to the narrowest channels of self-interest.

Put simply, we can shine a light on our denial and hubris.

Too often, as I have argued above, we forget where we are. Yet, if we were to see ourselves from space we could scarcely overlook the fact that we are all nodes in an evolving network. Though we may have a big impact on the workings of that network, it simply adjusts to our inputs. All the while this planet supports a biosphere its processes will continue and its balances regenerate. Considered whole, the biosphere is like a single cell, complete with an in-built ‘tweak’ mechanism (homeostasis) that maintains an equilibrium sufficient to ensure the survivability of the cell.

So, how is this relevant to politics? Setting aside standard ‘green party’ rhetoric, when we situate ourselves within the larger planetary/evolutionary context we glimpse an alternative politics: an ongoing, decentralised, multi-channel exchange that is both competitive and cooperative. As a system design, it offers us a valuable template for rethinking our own models.

- Error correction for fitness – optimising for survival – network resilience

- Branching networks – everything connected – organised but not centralised

What this illustrates is a model, a process, that is at once robust and fluid. Nature is always in beta mode; complexity in dialogue with entropy. System integrity is maintained not with hard borders and exact replication but with a mutating and porous interplay of multiple elements.

To some degree this biospheric blueprint is already evident in the arenas of politics, economy and culture, despite our habit of trying to impose tighter controls. That said, the ‘organisation’ of nature is more robust than any system thus devised by humans. Indeed, we may do well to harness our talent for mimicry in this instance. Or, at the very least, accept that no ideology or style of government is the finished article.

Therefore, as citizens in a vast and complex web of socio-economic exchange we cannot reasonably expect flawless government and unchanging conditions. Neither should we anticipate or wish for all laws to be set in stone. Nor should we view the task of government as being simple or ‘all about me & mine’.

Here again, nature hints at where our deeper, longer term self-interest lies. This is not to dismiss all short-term and partisan politics as entirely selfish and misguided, but to suggest that we should not take our eyes off the long game. Nor indeed forget what politics is actually about: namely, how can both individuals and tribes best live together, and how can we do so in an ongoing and sustainable way?

If we can wean ourselves off black/white reductions and the self-validating drug of other-blaming, we can perhaps begin to build consensus for a new practise of politics. One that is less about winning and empire, and more about the core survivalist imperatives of inter and intra-group organisation and resource management.

- I say can, not must, because, as with everything biospheric, humanity is neither a permanent fixture, nor essential. Our civilisation is an unfinished draft, our survival far from guaranteed. Perhaps we will ultimately predate on ourselves or trigger an extinction event. Or be enslaved by machines of our own invention. In the end it won’t matter. Even our future will be erased. All we truly have is a chance to choose. While we still can, how shall we go forward?

In all likelihood, we will never mimic the web of nature exactly, nor evolve a perfected system. However, I would argue that this is the precise start point for a more honest way of doing the unfinishable business of politics and governance.

11: Expectation management

So much of our disappointment arises because we have unrealistic – often unexamined – expectations. This is true in personal relationships and in our common framing of politics and society.

We see this reflected in the oft repeated talk-them-up/tear-them-down cycle. The fortunes and reputations of presidents, parties and policy platforms often swing wildly. Unfounded hope turns to exaggerated letdown, thence to scorn and a sense of decline and hopelessness. From there…perhaps extremism.

While some of this is fanned by the drama of media coverage, and by the theatrics of the players themselves, much of it stems from us. Specifically, from the evolved cognitive and perceptual biases discussed earlier. We are status quo preferring, coherence seeking creatures who like to belong, and who routinely stumble into the belief that things are going downhill. We also have a love/hate relationship with rules and authority. Much as we admire a fearless leader, we also like to blame them for everything.

Our ubiquitous anti-elite, anti-politician chorus is more akin to smug pubescent whining than well-reasoned, constructive critique. In our defence though, the incessant nature of the common complaint points to the measure of our shared disappointment. Although some of this is due to false (deceptive) promises and the ordinary human failings of parliamentarians, (including those of corruption and other vices), a large chunk of it arises because we arrive at the party with overblown expectations.

I realise it is no longer PC to question the supposedly sacred virtues and common sense wisdom of the nobly endowed 99%, but what if very few of us have any real idea what it takes to coach a topflight football team or steer a complex organisation, let alone consult with numerous stakeholders to draft passable legislation? Even if we think we can rule the world, chances are we would do so incompetently. Furthermore, we too would find it nigh impossible to resist the temptations that so often undermine the integrity of leaders and the regimes they represent.

In short, we now have inhuman expectations of our tribal elders. We project onto them our fantasy of perfect conduct and faultless intelligence, our child-like desire for benign, protective parent figures. (This goes some way to explaining our long running attraction to authoritarians.) Although we learn to forgive Mum and Dad their flaws, and hopefully extend the same compassion to ourselves, when it comes to the failings of distant, abstracted, dehumanised others – like foreigners and politicians – we are ruthless. We relish their downfall. It makes us feel superior.

See, told you so.

Yet, the trouble with fantasy is reality. Thus, while some will think me a tad harsh, I would argue that we are better off playing with the cards we actually have rather than those we wish we had.

The best way to reduce the cyclical drama of over-promise/under-deliver is to pay closer attention to expectation. Rather than simply sliding into the equally corrosive habits of cynicism and suspicion – or indeed the apocalyptic and jihadist manias of religious extremism and conspiracy paranoia – we can begin to build a base of trust rooted in a clear and universal acceptance. There will be bad apples, but the orchard remains fruitful.

12: Hawks & doves

Although we are all grounded in a common humanity, we are not all the same. Just as in other species, there are alphas. Moreover, our tribes are largely hierarchical.

Long before nation states, bureaucracies and corporations, there were vertical power structures. Through the lens of evolution, this is akin to a division of labour, or efficiency dividend – the group benefitting from the various contributions of its individual members, enabling them to tackle the widest range of tasks with the least amount of effort.

However, just as sociability is evolutionary, so is individual self-interest. A combination of natural and sexual selection processes underscore the powerful inclination we have to pass on our genes. Our idea of favourable characteristics.

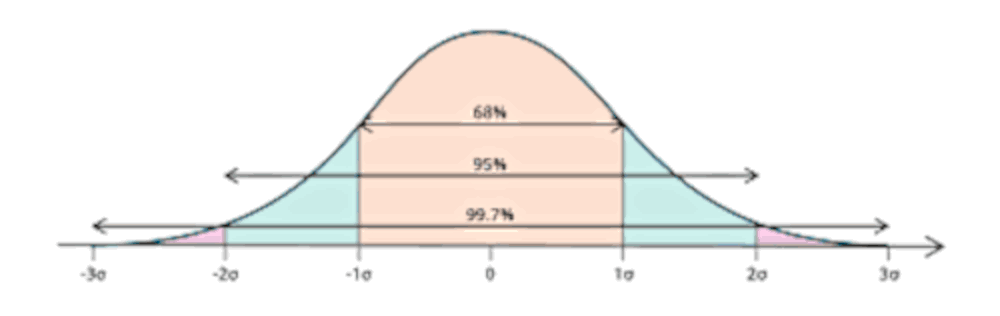

Therefore, although we are equally alive and just as dead, we are not equally talented, nor uniformly motivated. As many before have noted, there is a statistical distribution of abilities and proclivities across the population, famously represented by the bell curve (or standard deviation graph).

The majority of us live in the fat belly of that curve, nearer to the mean, with ever smaller numbers of us towards the flatter extremes on either side. Just as genius is rare, so too is murderous psychopathy.

Migrate this to the realm of politics and what we tend to see is a preponderance of individuals at the hawkish end of the spectrum – not necessarily war-like but driven and competitive. The same could be said for those who climb to the top of any large, complex organisation. Most of us simply do not have the will, the energy, or the steel to work our way up the ladders of hierarchy, let alone lead revolutions, grow trillion dollar companies or become a world number one. In truth, we probably lack the vision, the talent, or both.

- Sorry, folks – but the notion of the citizen polymath who knows better than every highly trained, vastly experienced specialist on the planet is more Mandela Effect than proof of the superiority of so-called common sense. You can call this snobbery if you wish. I prefer to call it nature. Again, one of the benefits of being a social animal is that our tribes (prides, herds, etc) leverage the natural variation of individual aptitudes within the group.

Although it is not a hard/fast rule, it is apparent that alpha bullies are better suited, temperamentally and morally, to ultra-selective arenas. Even if we cannot safely declare that all CEOs are psychopaths, and every politician a heartless, back-stabbing opportunist, it seems clear that a small number of hawks will almost certainly overwhelm a world of doves.

Therefore, when I argue that we ought not essentialise and dehumanise the political elite, I do so in the understanding that some humans have a competitive advantage; and since politics is notoriously and unforgivingly adversarial, we cannot reasonably remain blind to the likelihood that politics will produce hawkish victors.

The way to broaden the personality profile of the bearpit is to stop rewarding the biggest bullies and the most cunning liars. And that, dear reader, is down to you.

13: People power

As I suggested earlier, the best way to change politics is to change how we engage with it. Furthermore, to recalibrate the way we view ourselves, as individuals, as tribes, as a species.

In short, the psycho-politics I would like to move towards is emotionally intelligent, psychologically savvy and grounded in an honesty that transcends ideological simplification and hubristic fantasy, thereby allowing us to create something more fit for purpose than a race-to-the-bottom.

However, we cannot rely on misty eyed hope or noblesse oblige. Faith in Fuhrers rarely pays off. For politics to change, we need to change. Specifically, we need to take responsibility. After all, the power lies, as it always has, with the numbers. A single hawk may boss a hundred doves, but only because the doves cop it.

At present, as I have outlined above, we reward politicians by responding positively to their manipulations. Then, when Big Daddy fails to make us great again we whine like pissed off children until another abuser comes along to trump the former leader and lure us anew with a repackaged brand of false promise. All the while we reward predation, predators will apply for the job.

I do not mean to castigate, nor pretend I am not equally complicit. We all want the Mahdi or the messiah to arrive. We all love to snarl at bad guys and pretend that we wouldn’t do that. Yet, taking a breath and zooming out, we know that the saviour is a figment and that none of us are uniquely endowed with spotless virtue.

Thus, to turn numerical advantage into actionable people power we must stop lying to ourselves. Social and political norms arise from, and are reinforced by, the behaviours of individuals, just as individuals are nurtured in the seedbed of culture. While small, personal choices may not instantly move the needle, this is all most of us have in our locker. How do I behave? And what message does this send?

Part of being an adult is owning our actions and their consequences. The same is true in our role as members of the body politic. As the saying goes: shit in, shit out.

14: Conclusion

My intention here has been to focus more on identifying beginnings than prescribing specific outcomes. As such, the conclusion is the start.

- The true ground of politics is the tribe, and the negotiation of relationships within it

- The core task of politics is existential, deciding how best to meet pressing practical needs and preserve the longer term psycho-social wellbeing of the tribe

As such, politics and governance are less about perfection than adaptation. Both are largely reactive – responding to problems as they arise – but with a sideline in anticipating future challenges.

Each navigates complex terrain and operates against a backdrop of endemic uncertainty. In turn, the level of complexity and the number of unknowables increase as the tribe gets larger and group members are no longer connected by concrete, personal ties. What stories, what lore, can unify a city of strangers?

However, rather than using crisp, organisational logic we have approached the task in the messier manner typical of human beings. This is unlikely to change, certainly not while our politics remains wedded to a ‘lowest common denominator’ rationale.

Our challenge is to get the best out of the imperfect means at our disposal. In lieu of glorious revolutions and epochal paradigm shifts, we can start with changing the prism. What lenses do we look through when we think politics, governance and society?

I would suggest the following:

- Regard humanity in its evolutionary context – stop pretending to be outside of nature

- Reduce the clutter of rigid ideology – be less absolute about everything

- Filter for the distractions (and deceptions) of moral theatre – don’t fall for the same old tricks

- Be mindful of individual input – divorce righteous victim drama

To reiterate, psycho-politics is predicated on the personal. It begins and ends with how we choose to act, to respond, to relate. Individually. What market signals am I sending?

I have focused on this aspect of the body politic because it sits at the forgotten and unacknowledged centre of every human society. Language is the way we speak. Culture is a code of behaviour. Tradition is our habit. As such, politics and economy can be regarded as acts. Things we do. Civilisation is an epic improv, a theatre game still playing.

This is a departure from the mainstream of political thought, and one which some will doubtless regard as either unnecessary or missing the point. They would perhaps prefer a discussion about structural reform or economics. After all, we have big choices to make, with live debates about everything from the form and function of the state to the shifting landscape of rights and responsibilities. Indeed, we could conjure a long list of business pending, which is exactly what you would expect in a densely networked, inherently conflictual human ecosystem.

Thus, in the absence of the ideal we must work with the workable. And our materials are one another. If the arcane details and academic abstractions of policy formulation and standard political theory seem opaque, something over which we feel we have little or no impact, then we are left to find other means of influence.

On the surface, this appears naïve or impossible, if only because we are routinely swept up in the chant of powerlessness, repeating the us/them, master/slave mantra so often that it seems like hardwired truth. Then, in return for our victimhood, we are rewarded with righteousness. The slave is innocent, not culpable in the making of the mess. This is buck passing on a truly global scale.5

Why? Because we are not voiceless, and neither is the language of complaint the only viable option. Rather, the most potent form of activism available to us rarely occurs on the big stages of televised politics, nor even in the banner waving auditorium of protest and dissent. Our power is not dramatic but discreet. Private rather than public. Small actions making a massive impact.

Politics may well be an unwieldy group chat, but every one of us can choose how to participate. Although our letters to the president will likely remain unanswered, it is how we speak and listen to friends, family, work mates, etcetera that matter more.

This is what I mean by trickle up. Our power lies in how we treat one another and allow ourselves to be treated. If the megaphones are impelling us towards simplistic divisions and easy judgement, we can choose to reply with kindness. With suspended judgement.

Though true that any system will be gamed, and that there will always be those who seek advantage in predatory and unfair ways, (sometimes with recourse to cruelty), this does not dilute the power we all have at our disposal.

In essence, power is capacity; that which lies within the reach of intention. The power of our bodies to move, to manipulate objects. The power of our minds to imagine, to find solutions. The ability to be kind or cruel. Deny or accept. Blame or take responsibility.

So, to repeat, we may never wield formal political or institutional power, but we all have the capacity to change the tone of the discourse, to vote for a kinder world.

The bickerfest of standard ideology feeds on our attention, our repetition of its catch-all mantras and silver bullet prescriptions. Meanwhile, the political and technocratic class thrive on the exploitation of asymmetries and ingrained bias. Therefore, the first act of psycho-politics is to starve the status quo of oxygen. To harness the power of refusal.

Crucially, we do not need to stare down armies to do this. But we do need to hit pause on drama, blame, and apparent certainty. Remember, whoever the other is, they likely have more in common with you than either of you think. This becomes clear when we drill through our rationalised differences to locate the flawed and emotional wellspring of our unity. Even your enemy wants to be loved. To feel validated. To have a sense of agency. And avoid pain.

Politics may well be rooted in disagreement – and argument fundamental to resilience and adaptability – but the scale and temperature of that conflict does not necessarily have to lurch towards intemperance, absolutist assertion and holy war. It is within our power to disagree differently. To use our disputes as a gateway to understanding what sits at the heart of other people’s experience and worldviews, and thence to unearthing a deeper agreement.

But we must do this ourselves. We cannot continue to rely on tribal elders and saviours. Changing politics means changing our behaviour, our voice, on the ground. If all we do is whinge and play the poor me card we will continue to live in a disgruntled world, watching with increasing despair as ever greater numbers are seduced by extreme and cruel ideologies. And then what?

The active ingredient in psycho-politics is personal, everyday practise. If you want a better world – a more respectful, less exploitative brand of politics – lead the way.

- When we closely examine them, the divisions between us mostly melt away, and we cease to regard them as a prompt for prejudice and cruelty

- When we put ourselves in another’s shoes, we begin to see what lies behind their rationalised mask, and start to sense the emotional realities of their experience – just as we do with characters in movies

- When we remind ourselves that we share this space and its resources, that we are nothing without each other, it becomes easier to resist the gravity of greed and entitlement and to understand where our broader, deeper self-interest lies

Indeed, I would suggest that after raw survival our baseline self-interest resides in kindness. This does not require superior virtue, because kindness is practical. Moreover, political.

When the social contract and the basic tenets of civil reciprocity are being attacked by polarising politicians and religious fanatics, undermined by cruel and unsustainable economic practise, and further corroded by bias exploiting algorithms, the weapon of mass resistance is kindness.

Just as our biases and vices can draw us into downward spirals – where the kill or be killed mentality entrenches us in a cycle of mistrust and fosters a sense of decline – so too our better angels can nudge us into an upward spiral. Kindness will more often be met with kindness.

Humans are masterful mimics. We constantly mirror one another. We monitor and adjust our behaviours, often unconsciously, towards the norm. When avarice is the standard, we are more likely to be greedy. Likewise for kindness.

While political and cultural norms remain exploitative, setting a tone that is immature, selfish and exceptionalist, the bullies will prevail. Biggest egos, loudest voices, most guns. Breaking that cycle begins with your choice to extend kindness. To connect.

Some will wonder why I have spent 9500 words just to say be nice. Again, it is about power. What is within our capacity as single citizens? How we speak, how we listen, how we behave. These are our market signals, our demands.

If, as so many are saying, AI is going to take over much of what we currently do, what remains will be the act of being human. While this will still entail conflict, and some of us will continue to choose cruelty and prefer short-term, narrowly selfish options, it will also open up a new possibility. Namely, a chance to focus more on concrete networks of relationship, on the palpable enrichment that flows from kindness. From compassion and patience. From the vast mosaic of billions of flawed, incomplete and unique perspectives. The story we tell ourselves.

Our power is what we do. When we do it together our power base broadens. When we accept that no single solution is perfect, no outcome guaranteed, our power is more effective, better employed. When we own our power we reduce the likelihood of someone taking it from us.

So, please…hit the off button, draw breath, and be kind. I realise this is not a fully-fledged utopian vision or full proof plan for universal justice, nor an instant fix for all the maladies of a fractious world. Rather, it is my act of political kindness. My market signal. This is a politics I can truly engage in. A politics of deep humanity.

It may not be much but, for now, it is the only real power I have.

Postscript: A note on references

As I mentioned at the outset, I am not an academic and this is not a formal treatise. However, I have not simply plucked all of the above from thin air. Indeed, I have been slowly evolving my beliefs in this regard over decades, the process of which has been nudged along by many writers, thinkers, etc. Therefore, I owe a debt of gratitude to the following:

Hannah Arendt, Susan Cain, Eugenia Cheng, Richard Davies, Richard Dawkins, Robin Dunbar, David Eagleman, Niall Ferguson, Mohandas K Ghandi, Jane Goodall, Han Byeon Cheol, Andrew Huberman, Daniel Kahneman, Naomi Klein, Mark Manson, Felix Martin, Jordan Peterson, Thomas Piketty, David Pilling, Steven Pinker, Karl Popper, Bertrand Russell, Suzanne Simard, Joseph E. Stiglitz, Sun Tzu, et al.

Of course, I could go on; but the point here is not to validate my own waffle but to acknowledge that none of us think and act in a vacuum.

1: The Central Denial. Initially, in my 2019 book The Pointless Revolution, I defined it thus: Our universal proclivity to deny that we are animals and, hence, to pretend that we do not die. By denying our mortality we fundamentally divorce ourselves from ‘nature’ – which we then cast as an externality. Thus, by regarding death as our enemy we pathologise our essential human condition; and this often maps out in the punishment (sinner/victim) narratives of religion, the moralising control mantras of karma and custom, and the ‘immortality’ delusions of fame and legacy. In addition, it underwrites and legitimises all standard ‘life meaning’ tropes and the reductionist, pass/fail criteria they so routinely apply.

2: The science of the brain and human cognition are relatively new disciplines and, allied with advances in neuro imaging technology, have enabled us to better identify and quantify the specifics of our mental make-up. There are many books, podcasts, etc aimed at the non-academic that seek to unpack this. So please, don’t take my word for it – check it out for yourself. The journey into the brain is both fascinating and revealing.

3: The emergence of new AI technologies has been widely touted as seismic. Some predict extinction, others immortality. There are also those who believe that AI represents a step change in our evolutionary and/or spiritual trajectory. As I write – late 2024 – what seems clear is that the downstream of AI remains unpredictable. That said, it is very likely to have wide ranging impacts on the way we work, create, communicate, and practise medicine.

4: Although I believe that the pretence of powerlessness is mostly lazy and/or theatrical, I also acknowledge that this is a somewhat privileged viewpoint. I imagine that there are countless millions alive today – almost none of whom will be reading this – who do genuinely lack agency, or for whom any expression of such comes at great risk. To them, I bow.

5: See The Pointless Revolution for more on this. There I discuss the workings of what I call the ‘slave narrative’ in more detail.

RE: “Just as genius is rare, so too is murderous psychopathy.”

You’re obviously living in lala land. Repeating mindlessly what lala land has programmed you into.

By FAR the most vital urgent and DEEP understanding everyone needs to gain is that a mafia network of manipulating murderous PSYCHOPATHS are, and always have been, governing big businesses (eg official medicine, big tech, big banks, big religions), nations and the world — the evidence is very solid in front of everyone’s “awake” nose: see “The 2 Married Pink Elephants In The Historical Room”… https://www.rolf-hefti.com/covid-19-coronavirus.html

“When a well-packaged web of lies has been sold gradually to the masses over generations, the truth will seem utterly preposterous and its speaker, a raving lunatic.” — Dresden James

And psychopaths are typically NOT how Hollywood propaganda movies (or the Wikipedia/WebMD propaganda outlets) have showcased them. And therefore one better RE-learns what a psychopath REALLY is. You’ll then know why they exploit/harm everyone, why they want to control everyone and have been creating a new world order/global dictatorship, and many other formerly puzzling things will become very clear.

The official narrative is… “trust official science” and “trust the authorities” but as with these and all other “official narratives” they want you to trust and believe …

“We’ll know our Disinformation Program is complete when everything the American public [and global public] believes is false.” —William Casey, a former CIA director=a leading psychopathic criminal of the genocidal US regime

“2 weeks to flatten the curve has turned into…3 shots to feed your family!” — Unknown

“Repeating what others say and think is not being awake. Humans have been sold many lies…God, Jesus, Democracy, Money, Education, etc. If you haven’t explored your beliefs about life, then you are not awake.” — E.J. Doyle, songwriter

But global rulership by psychopaths is only ONE part of the equation that makes up the destructive human condition as the cited article above explains because there are TWO human pink elephants in the room… and they’re MARRIED.

Without a proper understanding, and full acknowledgment, of the true WHOLE problem and reality, no real constructive LASTING change is possible for humanity.

And if anyone does NOT acknowledge, recognize, and face (either wittingly or unwittingly) the WHOLE truth THEY are helping to prevent this from happening. And so they are “part of the problem” and not part of the solution.

If you have been injected with Covid jabs/bioweapons and are concerned, then verify what batch number you were injected with at https://howbadismybatch.com

“There are large numbers of scientists, doctors, and presstitutes who will sell out truth for money, such as those who describe people dropping dead on a daily basis as “rare” when it it happening all over the vaccinated world.” — Paul Craig Roberts, Ph.D., American economist & former US regime official, in 2024

“… normal and healthy discontent .. is being termed extremist.” — Martin Luther King Jr, 1929-1968, Civil Rights Activist

LikeLike